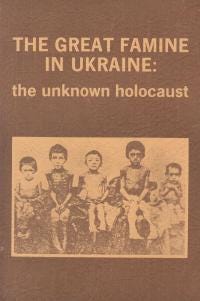

24. The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust

Chapter Three - Famine Photographs, Which Famine?

As noted in the previous update of The Red Report, Douglas Tottle, in his third chapter, challenges three texts for their misattribution of the already troubling Dittloff images included in Ewald Ammende’s Human Life in Russia. The second of the three works set for examination is The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust, first published in 1983.

Compiled by the editors of the Ukrainian Weekly and published by the Ukrainian National Association, The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust contains a number of essays by academics including James E. Mace and Marco Carynnyk. The book also contains both survivor and press accounts of the famine, as well as a section on the famine as seen through the eyes of Soviet dissidents, such as General Petro Grigorenko. Originally published in 1983, The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust was reissued in a second edition five years later in 1988.

In addition to the essays and various accounts of the famine in The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust, the text includes two newspaper reproductions, of three and five photos, respectively, as well as seventeen individual photographs. In total, there are twenty-five images attributed to the famine in the book, plus the cover photograph. Of those twenty-five images, four are duplicates. This means that there are twenty-one unique images to be found within the text, along with the front cover.

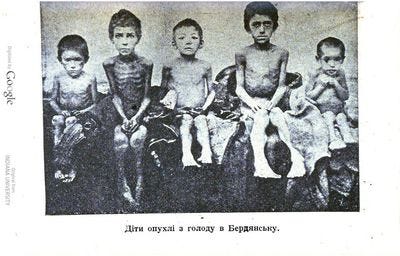

Tottle notes that the images used in this book are either uncredited or attributed to Thomas Walker (Tottle 29). This is correct. Of the twenty-one original photographs, fifteen are attributed either explicitly to Thomas Walker, or to the New York Evening Journal, which carried his reporting. From these fifteen images, ten appear credited to Dittloff in Human Life in Russia, while the remaining five are either from Daily Express articles, or may be original photographs or photographs yet to be attributed to a third party. Discounting these fifteen images leaves six remaining. Two of these six are depictions of famine victims from the 1920s; two more are photographs by Alexander Wienerberger and are featured in Ewald Ammende’s original text, Muss Russland Hungern?; one image is found only in Human Life in Russia and attributed to Dittloff; and one appears to be of unknown origin. It must also be noted that the cover photo is also used in Human Life in Russia, but actually depicts famine conditions in Ukraine during the 1920s rather than the 1930s.

It is plain to see that, with regard to the images used, The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust is a convoluted text and Tottle is right to point this out. However, there proves to be something equally as perplexing on Tottle’s side that is evident only when examining the note accompanying this section of his book. On page 144 of Fraud, Famine and Fascism, note 27 reads:

[The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust] is illustrated entirely with famine photographs plagiarized from the World War I to 1921-1922 Russian famine era. (Tottle 144)

As previously mentioned, two of the images in The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust have been verified as taken between 1921 and 1922, as has the cover photo. Tottle correctly points this out in his note, too. However, he fails to mention that the cover photo was taken in Ukraine and not in Russia (fig. 2; “Non-Holodomor”).

Tottle also offers no indication as to which of the photos come from the “World War I… era”. Moreover, an observant reader will notice that Tottle’s claim in the above quotation is patently false, as it has earlier been established that two of the images present in The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust were taken by Alexander Wienerberger—a fact to which Tottle does allude (Tottle 29)—and, therefore, are neither from the periods 1914-1918 or 1921-1922. Having had access to Muss Russland Hungern?—a text he largely ignores—Tottle would have been aware of this, yet proceeded to make such a claim, regardless.

Furthermore, Tottle appears to have had access to the Daily Express articles from August 1934, whose reporting predates that of Thomas Walker, and whose images also feature in The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust. Why Tottle would claim that all the images in The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust are either from World War I or the 1921-1922 famine when it is apparent that they are not is both difficult to establish and highly curious. There is also a certain irony present, as Tottle’s central argument here is in regard to poor scholarship and the misattribution of photographs yet he, himself, is guilty of both.

Finally, it should be noted that Tottle makes no attempt to challenge any of the writing presented within The Great Famine in Ukraine: The Unknown Holocaust. In fact, nowhere else in Fraud, Famine and Fascism is this book raised but in this third chapter.

Work Cited

“Non-Holodomor: Five Boys in Ukraine, Stripped Down and Seated in a Row, Showing Evidence of Starvation and Swelling.” Holodomor Research and Education Consortium, https://vitacollections.ca/HREC-holodomordigitalcollections/3636151/data?n=1. Accessed 8 Jul. 2023.

Tottle, Douglas. Fraud, Famine and Fascism: The Ukrainian Genocide Myth from Hitler to Harvard. Progress Books, 1987. www.archive.org/details/DouglasTottleFraudFamineAndFascism. Accessed 1 Sept. 2022.